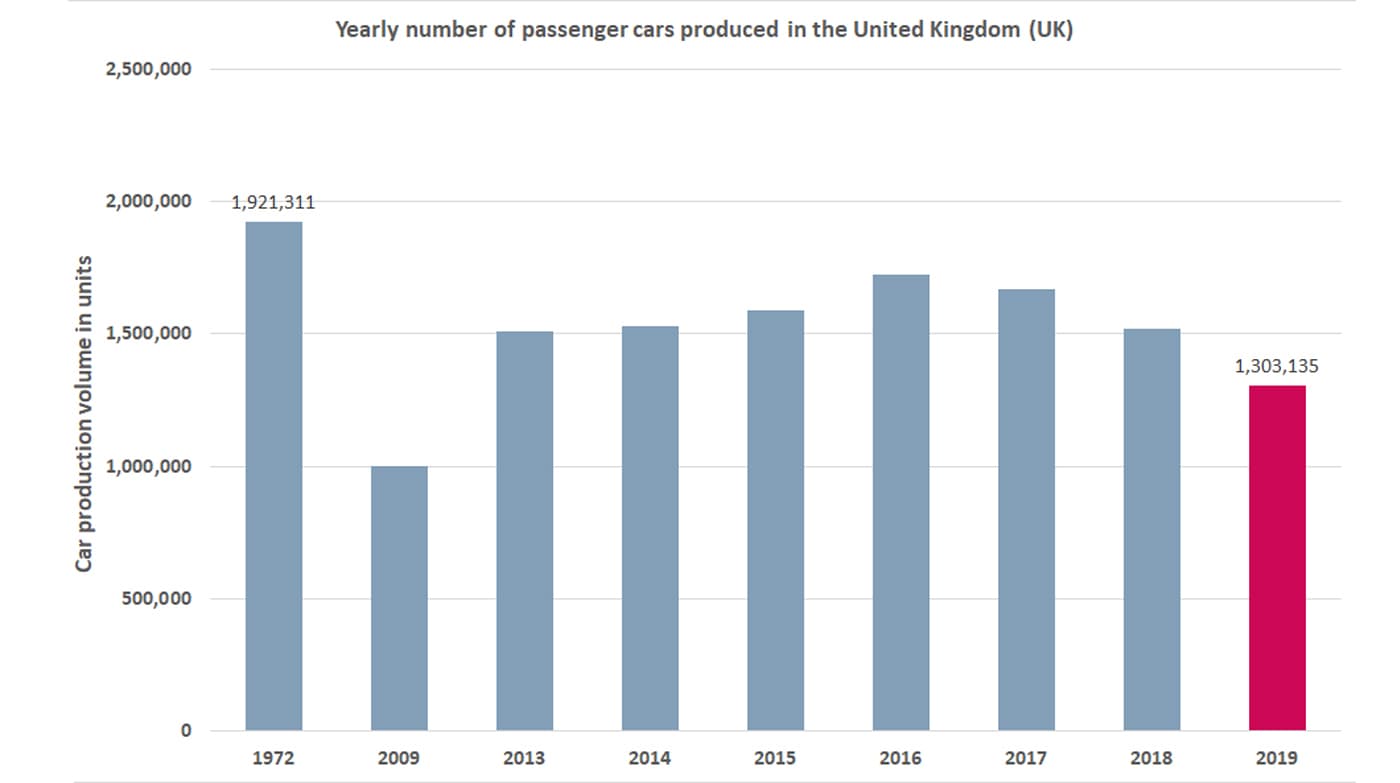

The latest independent outlook for the UK car manufacturing industry predicted that factories will make fewer than 885,000 cars this year — the first time volumes will have dipped below the one million mark since 2009. The one bright spot is EV manufacturing. In September 2020, production of the latest electric vehicles (EVs) in the UK grew by 37% year-on-year[1]. However, with the global shift to electric vehicles the UK risks falling even further behind in terms of vehicle production. The Government has said it wants to “cement the UK’s position as a world leader in low emission and electric vehicle industry” but at the moment, we’re far from leading the market in EV production.

At first glance, the UK’s automotive headline stats appear respectable. According to the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), the UK is currently the fourth largest automotive manufacturer in Europe, having manufactured 1.3m and exported 1.05m cars in 2019 (accounting for 14.4% of total UK exports). The industry had an £82bn turnover in 2019 and added £18.6bn of value to the UK economy, making it one of the nation’s most valuable economic assets[2].

There were 11 engine manufacturers that built over 2.5m engines in 2019 and six mainstream car manufacturers in the UK. The SMMT also reported that the UK is home to more than 60 specialist car manufacturers, seven major premium and sports car manufacturers, eight bus and coach manufacturers and four commercial vehicle manufacturers in their latest Motor Industry Facts 2020 report[3].

However, it’s important to view these headline figures in context. In 1955, the UK became the world’s second largest car manufacturer but in 1972 car manufacturing in the UK peaked, producing approximately 1.92m units. A perfect storm of adverse conditions hit the industry in the 1970s, and by the early 1980s production had nearly halved to just over 1m units. Increased competition from foreign-built motors (particularly German and Japanese models), production and supply chain issues, industrial action and quality issues plagued the sector during this period.

The UK's status as a major manufacturer declined largely due to higher unit costs when compared to production in other countries. Over time, the UK began to lose its British-owned motor vehicle industry. Factories and plants located in the UK became part of the global supply chain of foreign companies. Now, just three auto manufacturers remain fully British-owned: McLaren, Caterham and Morgan.

Powering up a British manufacturing boom

The UK has a growing EV manufacturing base, but there is a fear that as vehicle manufacturers wind down internal combustion engine (ICE) production and instead focus on producing greater volumes of EVs, the high cost of importing batteries will diminish the commercial case for producing cars within the UK.

In a bid to drive down costs and simplify supply chains, EV and battery manufacturers prefer to co-locate production. Indeed, the former CEO of the Faraday Institution Neil Morris suggested that one of the key criteria that battery manufacturers consider when placing a battery factory is proximity to car manufacturing. The UK has a strong manufacturing platform to build on and it is accompanied by a strong research base which should help entice EV manufacturers, but there has to be the necessary battery manufacturing capacity to support them in making more EVs in the facilities they have.

"One of the key criteria that battery manufacturers look to when placing a battery factory is proximity to car manufacturing"

It is both challenging and costly for traditional auto manufacturers to adapt their existing facilities to accommodate EVs. Traditional manufacturers are also hindered by commitments to continue selling ICE vehicles, which is where most of their revenue comes from. Whilst EVs benefit from a simpler structure and contain fewer components, EVs currently cost more to produce than ICE vehicles and are likely to remain more expensive to produce for at least a decade. Although recent analysis suggests that the total cost of manufacturing a compact emissions-free for European carmakers is expected to fall by more than a fifth by 2030 (to €16,000), this will still represent a 9% premium when compared with petrol or diesel models[4].

As vehicle manufacturers focus their investments on fine-tuning the production lines for EVs, production costs will continue to fall. For now though, most manufacturers don’t make a profit from the sale of EVs because they cost significantly more to produce than comparable ICE vehicles. One of the reasons for this is that very few manufacturers currently use a purpose-built EV platform to assemble the vehicles. Instead, they tend to use complex multi-powertrain platforms that combine ICE vehicle and EV lines. These complex plants are more difficult to assemble and have higher fixed costs[5]. Whilst this set-up is understandable as manufacturers continue to build both ICE vehicles and EVs, they will ultimately need to retool their plants using dedicated electric vehicle architecture.

Increasingly, batteries, electronics and electric motors will take the place of transmissions, exhausts and internal combustion engines. Powertrain elements that were previously produced in-house may be outsourced and supplied by external companies that specialise in individual components such as semi-conductors. Manufacturers will need to adapt/convert their assembly lines and use of existing factory space accordingly. With the possibility that new sales of petrol and diesel vehicles will end in 2035 and given the lead-times involved, some manufacturers won’t be far away from ceasing investment in new production lines for ICE vehicles.

Based on its expectation that demand for traditional combustion engines will decrease, Daimler announced that it is in discussions with German labour unions (as the move may result in some job losses) to convert key engine and transmission factories in Berlin and Stuttgart for the EV era. Daimler intends to transform its powertrain division toward ‘electric first’ by expanding electric-mobility operations in Stuttgart whilst its smaller Berlin plant will focus on electric and digital components[1]. Given that EV powertrains are less mechanically complex than ICE powertrains, EV assembly lines can be simplified and automated to a greater degree. As more manufacturers retool for EV production (whether it be using ‘electro-only platforms’ or integrated production lines capable of assembling multi-powertrain vehicles), space requirements are likely to change.

Almost all major car manufacturers have ambitious plans for the EV market and are heavily investing in factories to meet forecast consumer demand. Although manufacturing EVs requires fewer mechanical parts than ICE vehicles, they do require a large number of new electric components – including battery cells (the basic unit of a lithium ion battery). The production of battery cells, which are used to make ‘battery packs’, are challenging to transport, which means that production ideally needs to be close to vehicle assembly. Currently, the bulk of battery cell production is located in Asia, making the import of the lithium ion batteries both costly and carbon-intensive.

For the EV manufacturing industry to really thrive in the UK, it’s widely acknowledged that battery cell production needs to be brought closer to home.

Even if cell manufacturing cannot be moved in-house (ie ‘vertical integration’), vehicle manufacturers would benefit greatly from partnerships with local battery cell manufacturers. Without a large-scale onshore battery production supply chain in the UK, domestic EV producers are likely to gradually wind down production.

G&T’s long history of constructing manufacturing facilities

G&T has been involved in several major projects for UK manufacturers over the years. G&T provided Cost Management services on McLaren’s state-of-the-art production centre at their HQ in Woking. The centre was originally used for the manufacture of the McLaren MP4-12C supercar (now out of production) but is now being used for all McLaren road cars. The project, designed by Foster + Partners, includes a tunnel from the existing McLaren Technology Centre (MTC), a VIP mezzanine level and a basement. The production centre is concealed within the green belt landscape and was designed to be environmentally efficient, incorporating a low-energy system of displacement ventilation. The roof also collects rainwater and its design will enable the installation of photovoltaic panels in the future.

G&T has also provided Construction & Property Tax Advice to Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) on its i54 site in Pendeford near Wolverhampton. The project comprised a new mechanical hall and engine assembly workshop (Module 1) of approximately 73,000m². The scope was subsequently extended to include an additional assembly workshop on the site (Module 1A). The two main buildings - the machine hall and the assembly hall - are divided by a third building which accommodates the main reception area, conference and exhibition space, staff and visitor restaurant as well as general offices and meeting rooms over two storeys.

G&T has also been involved in developing advanced engineering centres (AECs) for higher education institutions such as the one at the University of Brighton. The AEC facility was built to support business investment, create employment opportunities and deliver academic excellence in the field of advanced automotive engineering. The facility has enabled the expansion and enhancement of the existing partnership with Ricardo (a global strategic engineering and environmental consultancy) in the design and development of innovative, low carbon combustion engines. The AEC has also enabled the advancement of technological knowledge and support the training needs of the next generation of engineers.

Battery Manufacturing

Battery manufacture capacity

One of the biggest constraints on the global adoption of EVs is that there is simply not enough battery manufacture plants to meet demand. While range and price are certainly significant constraints to EV take-up, it is battery manufacture capacity that will enable mass adoption.

There is a huge rush to build gigafactories that can remedy the current lack of battery manufacture capacity. Gigafactories are therefore set to make a big impression in the UK’s industrial property landscape as it steps up battery manufacture capacity to meet domestic demand.

At present, the battery manufacture market is dominated by players from just three countries – China, Japan and Korea. According to McKinsey, in 2018, less than 3% of the total global demand for EV batteries was supplied by companies outside these three countries and only approximately 1% was supplied by European companies. However, they note the potential battery market in Europe is huge. By 2040, McKinsey’s base scenario projects that battery demand from EVs produced in Europe will reach a total of 1,200 gigawatt-hours (GWh) per year, which is enough for 80 gigafactories with an average capacity of 15 GWh per year.[7]

With projected battery demand from European produced EV’s being more than five times the volume of currently confirmed projects in Europe, the additional demand will have to be met by either battery imports or by adding further manufacturing capacity in Europe. Local battery production is preferred as it removes significant supply-chain risks for OEMs and from a governmental perspective, with the battery making up 40% of an EV’s value[8], it means that a large share of the value chain is captured domestically. It also enables the creation of a complete research and innovation ecosystem, fostering co-development among players in EV production.

In its March 2020 report[9], the Faraday Institution’s battery demand forecast model projected that under its central scenario, UK EV battery manufacturing capacity in 2040 will be around 140 GWh per year – around 12% of the projected 1,200 GWh per year European battery manufacturing capacity in 2040.

However, this would mean that over the course of the next 20 years, the UK would have to build about seven battery production plants (or “gigafactories”), each producing on average 20 GWh of battery capacity each year.

By way of reference, a single 20 GWh factory would be capable of producing batteries for 500,000, 40 kWh Nissan Leafs per annum. If all seven UK-based gigafactories were to only produce batteries for the 40 kWh Nissan Leaf, the UK would be able to support the production of 3.5m Nissan Leafs annually. This puts annual EV production well above Faraday’s projection that UK automakers will produce 1.6m EV’s per year by 2040. However, a 40 kWh battery is considered to be relatively small compared to the current average capacity of full EV models (which, according to some sources, is currently around 60 kWh[10]) and EVs are increasingly using larger batteries to maximise their range.

Faraday note that establishing seven gigafactories would require an investment in the range of £12bn but caution that the window of opportunity to build these gigafactories is closing rapidly. Although building battery production facilities present a considerable industrial opportunity for the UK, it takes between five to seven years (from planning to reaching full operational capacity) to build a battery-manufacturing plant and many domestic EV manufacturers have already negotiated long-term contracts with battery suppliers outside the UK, diminishing the chances of securing UK gigafactories (and hence the chances of sustaining an EV production industry in the UK).

Supply Issues

Battery cell manufacture currently faces a chicken and egg situation. The Lithium-ion battery is currently the default EV battery. The three main components are lithium, nickel and cobalt, however the supply of cobalt appears to be acting as a limiting factor in battery cell manufacture. Cobalt mines won’t open and increase the supply of the element until there is greater demand from battery manufacture plants. Cobalt’s scarcity has led to higher battery cell manufacturing prices and many battery manufacturers aren’t keen to develop production plants until the price of price of battery cell manufacture comes down.

Battery cell manufacture capacity inevitably dictates the production capacity of EVs. China, which has the biggest demand for EVs globally, owns 80% of the world’s total output of raw materials for advanced batteries. Furthermore, of the 136 lithium-ion battery plants in the pipeline to 2029, 101 are based in China[11]. The country controls the processing of almost all the critical materials for battery cell manufacture and is therefore able to dictate key raw material prices.

In China, 6% of a car manufacturer’s annual output must be from EVs, otherwise they can’t sell ICE vehicles in China. This has a significant impact on battery cell availability outside of China as manufacturers are pressured to meet this target by re-directing EVs manufactured in the UK and other countries to China as it is the world’s largest market. As the UK has sold much of its car manufacturing industry to China, it has very little say over what gets made in the UK and where it goes. If the UK government is to meet its ‘Road to Zero’ targets for EV sales in the UK[12], then it will need to build battery production facilities in order create its own supply of battery cells.

Case Study: Britishvolt

A UK-based company called Britishvolt is dedicated to supporting the future of electrified transportation and sustainable energy storage. Its aim is to establish the UK as the leading force in battery technology, producing world-leading lithium-ion battery technologies for EVs. The company has chosen the UK for its investment in battery technology due to its strong automotive and energy industries, supported by its strong history of academic research and development.

In July 2020, Britishvolt confirmed plans to open the UK’s first full cycle battery cell gigafactory in collaboration with Pininfarina, which will design the plant. The 2.7m sq ft plant will have an annual battery production capacity of up to 30GWh, giving it an output on a par with Tesla's Gigafactory in Nevada, US. The gigafactory, which will have one of the top three largest single footprints in Europe, will be powered by renewable energy to help support sustainable production of the batteries. G&T is providing cost management services on this landmark project.

Construction of the manufacturing facility is slated to begin in Q2 2021 and Britishvolt aims to open the facility in 2023.

The project will become one of the largest industrial investments in British history and will make Britishvolt a global leader in the production of high-performance lithium ion batteries. The gigaplant will help power the electric revolution and will meet demand for onshore battery production in the years to come. It will also make Britain less dependent on overseas supply and secure the long-term prospects of the UK car industry, which was suffering from a fall in production even before the pandemic.

The future of the UK automotive industry

It’s been established that there are clear benefits in locating vehicle manufacture plants close to battery manufacture plants. If the UK is to take back control of its automotive future and achieve its political aspirations with regards to EV uptake, then the gigafactories required to produce battery cells and assemble EV batteries need to be located in the UK.

The transition from ICE vehicles to EVs places the entire UK automotive industry at risk. In the worst case scenario, a lack of investment in UK battery production gigafactories is likely to mean that vehicle manufacturers will gradually reduce their ICE (and EV) production facilities and the 168,000 people directly employed by them[13]. Without any UK gigafactories producing batteries and associated EV manufacturing, Faraday forecasts that direct automotive employment would be 105,000 lower in 2040 than it would otherwise be[14]. Insufficient investment will see vehicle production volumes fall, setting the UK on a path where it ceases to become a manufacturer and exporter of vehicles and instead becomes an importer.

Conversely, the global transition to EVs also presents a massive opportunity for Britain’s automotive and manufacturing industries. Some upside scenario forecasts suggest that the UK, with the right partnerships and investment, could become a leader in producing batteries and EVs, greatly expand its global market share and substantially increase vehicle production. However, establishing the UK as a European centre for battery and EV production will be challenging. Instead, the Faraday Institution has generated a more realistic base case or ‘central scenario’ projection – a scenario which would see battery pack, battery cell and electrode manufacturing all located in the UK.

Under its central scenario, the UK will be producing nearly 1.6m EVs per year by 2040. However, production at this level will almost certainly necessitate the establishment of a secure domestic EV battery supply. Faraday’s demand forecasting model projects that battery manufacturing capacity will need to be approximately 140GWh per year. This is the equivalent of building seven gigafactories in the UK, each producing an average of 20GWh of battery capacity per year. Such a scenario would support a 29% growth in the overall industry workforce of the automotive and EV battery ecosystem by 2040 with

- 78,000 new jobs created in the new UK battery gigafactories and in their battery material supply chains

- 32,000 jobs remaining in ICE vehicle production

- 110,000 jobs remaining in powertrain manufacturing serving both ICE and EV production

However, establishing these seven gigafactories will only sustain a level of EV production in the UK that is equal to the UK’s current share of the ICE market. Simply put, increased funding and investment will be necessary just to stand still. Other countries and governments are working hard to secure a new battery manufacturing industry by creating favourable business conditions to attract manufacturers. Stakeholders in the UK will need to act quickly in the race to develop a large scale domestic EV battery supply through the required investment in new factories.

Fortunately, the UK government sees this as a strategic priority, but time is of the essence for both the Government and industry leaders to establish UK gigafactories and secure the future of its automotive industry.

In this shifting landscape the automotive industry is now facing one of the biggest challenges it has seen in decades. G&T has a wide range of project experience in the automotive manufacturing sector and is able to provide expert advice to clients looking to build, expand or repurpose their existing auto manufacturing plants and facilities. To discuss your particular project requirements or find out how we can add value to your project, please contact Jason Fowler - Partner at G&T.

[1] https://www.cityam.com/car-ind...

[2] https://www.smmt.co.uk/industr...

[3] https://www.smmt.co.uk/wp-cont...

[4] https://www.ft.com/content/a7e...

[6] https://europe.autonews.com/au...

[7] https://www.mckinsey.com/indus...

[8] https://faraday.ac.uk/wp-conte...

[9] https://faraday.ac.uk/wp-conte...

[10] https://ev-database.uk/cheatsh...

[11] https://www.benchmarkminerals....

[12] The strategy sets out the intention that at least 50%, and possibly as many as 70%, of new vehicle sales in 2030 will be of ultra-low emissions models. The government has also recently announced a consultation on bringing forward the end of the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans from 2040 to 2035.