Ireland’s rail system is on the brink of its most ambitious overhaul in generations. Driven by the All-Island Strategic Rail Review (AISRR)[1], this transformation envisions a faster, greener and more connected future for both passengers and freight. The plan sets out to electrify key routes, reinstate disused lines and expand services to underserved regions—all while aligning transport investment with climate action, economic resilience and spatial equity.[2]

But delivering this vision is far from straightforward. Funding constraints, complex planning processes and capacity bottlenecks will test the resolve of policymakers, clients and contractors alike.

In this article, we explore how rail infrastructure renewal can underpin Ireland’s broader environmental and economic objectives, while interrogating the risks, trade-offs and delivery complexities that lie ahead. Drawing on the latest strategic reports, expert commentary and G&T’s experience delivering complex rail and infrastructure programmes, we examine how a new age of rail could reshape mobility, sustainability and opportunity across the island. We have previously provided procurement advice to Transport Infrastructure Ireland, a state agency under Ireland’s Department of Transport, and bring insight into the institutional and delivery landscape this transformation must navigate.

The Current State: Fragmented, Underused, and Dublin-Centric

Ireland’s railway, much of it a vestige of Victorian engineering, is both spatially fragmented and chronically underutilised. With just 2,400 kilometres of operational track[3], the network ranks among the least extensive in Western Europe. The figures are stark: rail accounts for only 1.6% of total passenger journeys, compared with over 8% in France and the Netherlands[4]. Freight usage is similarly marginal, with less than 1% of goods moved by rail[5]. This places Ireland at the very bottom of the EU rail freight league, a status quo the AISRR describes as 'significantly eroded' and economically unsustainable.

The network’s radial design—with Dublin at its hub—limits regional connectivity. While intercity travel is relatively efficient, the absence of lateral connections inhibits movement between regional centres. Areas such as the north-west and western seaboard are effectively rail deserts, with little to no rail infrastructure. Meanwhile, cities like Limerick, Galway and Sligo do have rail connections, but their poor interconnectivity with other regional centres inhibits growth and reinforces Dublin's economic dominance.

Expert voices in recent commentary emphasise that a modern economy requires an integrated, high-frequency and equitable transport system. Without a shift away from car dependency, Ireland risks locking in congestion, emissions and regional disparity.

Electrification and Climate Alignment

Decarbonisation sits at the heart of the Strategic Rail Review. Ireland’s legally binding targets—51% emissions reduction by 2030 and net zero by 2050—necessitate a modal and technological shift. Today, diesel trains dominate the network, with their associated emissions, noise and operating costs. The electrification of high-demand routes such as the Dublin-Belfast corridor, Cork-Dublin line and Dublin-Galway axis is therefore a central policy plank[6].

Ireland has the lowest level of electrified railways in the EU, and Northern Ireland has none. As the AISRR notes, this structural deficit not only threatens climate goals but weakens rail’s competitiveness relative to road-based modes.

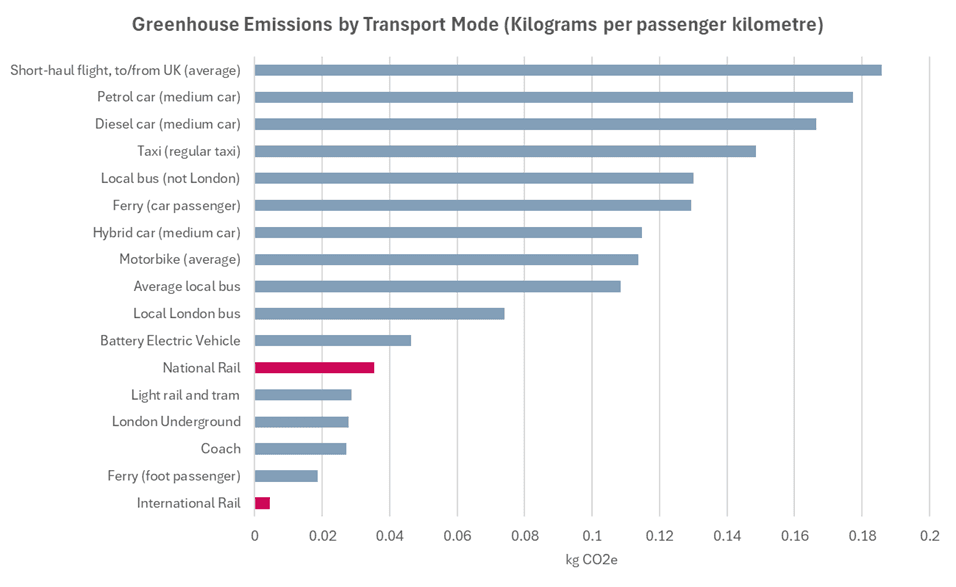

Rail's environmental credentials make it uniquely well-suited to support this transition. As the chart below illustrates, rail emits significantly less greenhouse gas per passenger kilometre than private cars, buses or short-haul flights.

This performance advantage strengthens the case for rail investment as a cornerstone of Ireland’s wider decarbonisation effort.

But electrification isn’t just a technical fix—it’s a policy and delivery challenge. According to the Department of Transport, full electrification will require a major upgrade to Ireland’s grid infrastructure, long-term procurement pipelines for rolling stock and a rethinking of how investment is phased. It’s also worth noting that rail will be competing with other demands on electricity supply—including data centres, residential development and industry—which may further complicate delivery and grid planning.

Experts have cautioned against a stop-start approach, citing international evidence that underscores the need for a rolling electrification programme. Such a programme can reduce unit costs over time, build supply chain maturity and sustain delivery momentum.

Battery-electric and hydrogen hybrid systems are also being explored to complement traditional electrification—particularly on routes where full electrification via overhead lines may not be viable in the short term. These technologies offer a flexible, lower-carbon alternative that can extend the network’s reach and reduce emissions on both lower-density rural lines and suburban services.

In the short term, Irish Rail has committed over €600 million to a new fleet of electric and battery-electric trains, with the first units entering service by 2025[7]. These battery-electric trains will initially be used on partially electrified routes, allowing flexible operation until full infrastructure is in place. Meanwhile, the DART+ programme—a major expansion of Dublin's suburban rail network—is being hailed as a testbed for scaling electrified commuter rail. It includes planned extensions to Maynooth, Hazelhatch and Drogheda, and aims to double capacity and triple the extent of electrified rail in the Greater Dublin Area[8].

Ireland’s electrification strategy will need to strike a careful balance between ambition and realism. Delivery can be de-risked by ensuring that grid upgrades are aligned with rolling stock procurement and that the sequencing of works follows a coherent, integrated plan.

Reconnecting Regions and Driving Spatial Equity

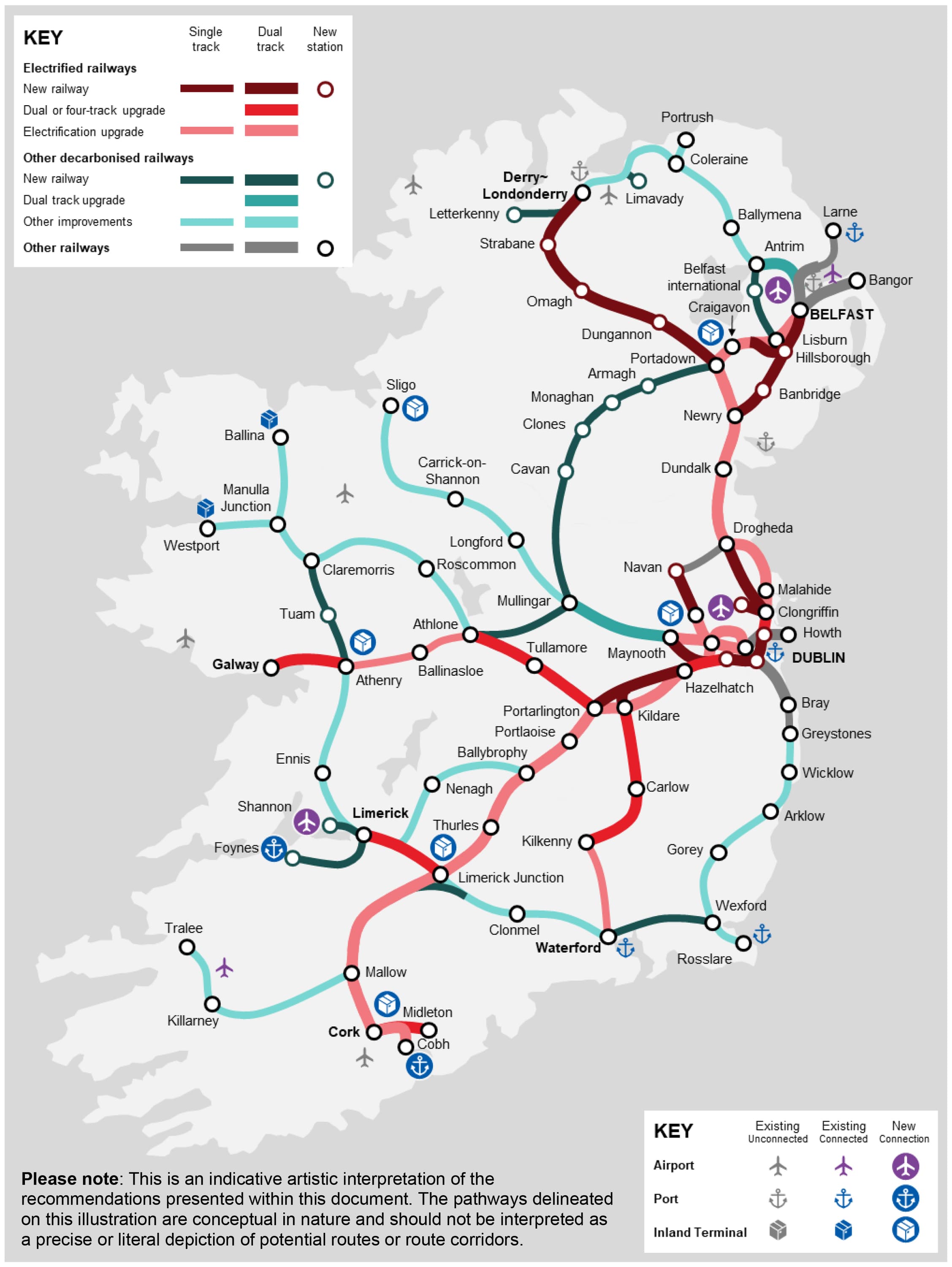

The AISRR identifies significant opportunities to address Ireland’s spatial imbalance. New and reinstated lines—such as the Western Rail Corridor (linking Galway to Sligo via Claremorris), the Wexford-Rosslare line and the long-stalled Navan-Dublin link—could unlock development potential in areas traditionally neglected by national infrastructure planning[9].

Indicative pathways for new, electrified, and upgraded rail lines across Ireland as proposed in the All-Island Strategic Rail Review.

Improved rail access could also play a role in alleviating housing pressures. As cities like Dublin and Cork grapple with unaffordable rents and limited supply, enhanced commuter rail links would make satellite towns more viable places to live, thereby supporting balanced regional growth. Recent stakeholder submissions to the review argue for rail as a lever of spatial equity—connecting people to opportunity and revitalising local economies.

Encouraging modal shift will require more than infrastructure. Affordable fares, seamless multimodal ticketing and good first- and last-mile links must be embedded to make rail a practical alternative. Without these, even enhanced services risk underuse.

On the freight side, industry bodies such as the Freight Transport Association (FTA) Ireland have called for a revitalised national freight strategy[10]. This would entail upgrading sidings—the auxiliary tracks that allow freight trains to be loaded, unloaded or stored without disrupting mainline services—and investing in intermodal terminals, which enable efficient transfer of goods between rail and road transport, such as at Foynes and Ballina. These interventions, alongside incentives to shift bulk goods off the road, could significantly enhance the competitiveness and carbon performance of Ireland’s freight system.

The 2040 Rail Freight Strategy[11] aims to raise rail freight’s mode share to 5–10%—closer to peer island or peninsula states in Europe. This will require terminals in places like Athenry, Limerick Junction and west of Dublin, alongside pricing reforms (to ensure competitiveness with road freight) and port connectivity upgrades (to ensure seamless movement between Ireland’s busiest ports and inland terminals)[12].

Rail freight, although currently minimal, could become a vital component in decarbonising logistics, especially for construction materials, agriculture and port traffic.[13]

Delivery Risk and Institutional Readiness

The AISRR’s vision comes with a hefty price tag. Early estimates place the cost at €35-37 billion[14] over three decades—a figure that dwarfs existing transport capital budgets. Funding from the European Union’s TEN-T and Connecting Europe Facility schemes could help, but the bulk will likely fall on domestic sources, requiring political will and fiscal discipline.

But capital alone is not enough. Institutional capacity presents a parallel challenge. Delivering the rail transformation will require unprecedented coordination between Irish Rail, Transport Infrastructure Ireland and the National Transport Authority—each with overlapping mandates but limited shared delivery infrastructure. Planning delays, already commonplace in road and housing schemes, risk spilling into rail unless systemic bottlenecks are addressed.

Institutional fragmentation and the absence of a dedicated long-term delivery mechanism present real risks to the successful implementation of Ireland’s rail strategy. One possible solution would be the creation of a central delivery body to coordinate across agencies, phase works strategically and build delivery capability at scale. Some experts advocate for an independent rail delivery authority—akin to Crossrail Ltd or Sydney Metro—operating beyond electoral cycles, with long-term funding and commercial oversight.

As echoed in the Irish Academy of Engineering’s recent analysis[15], governance reform must go hand in hand with capital investment if Ireland is to avoid the pitfalls that have beset other major infrastructure programmes. Many large projects fail not due to a lack of vision, but because the delivery ecosystem isn’t equipped to execute them. Ireland must invest not just in concrete and steel, but in the programme management expertise required to turn strategy into execution.

Addressing these institutional and delivery challenges will require not only governance reform but also the implementation of robust programme management frameworks and assurance processes—especially on large, multi-phase infrastructure schemes.

At G&T, our Portfolio and Programme Management services help public sector clients navigate exactly these kinds of complexities. We take a strategic view to ensure that Capital Investment delivers defined objectives, benefits and improvements to our clients’ operations and provide delivery model, commercial and procurement strategy advice to ensure clear and performance driven progress. Furthermore, implementing robust control processes and procedures is a way to ensure projects and programmes, particularly complex ones, deliver expected outcomes and manage exposure to risk.

For example, through our work with Transport for London (TfL) under its Professional Services Framework 2, we have provided Project Management, Programme Controls and Independent Assurance services to support delivery across its ambitious capital investment programme. This has included the development and implementation of consolidated reporting systems and process on a major programme of work, the provision of specialist expertise to strengthen TfL’s PMO across planning, project controls and risk management as well as the delivery of numerous independent assurance reviews across a range of capital investment works including road, rail and technology.

Lessons from this kind of work, where complexity, interdependence and stakeholder scrutiny are high, are highly relevant as Ireland gears up to deliver one of the most ambitious rail programmes in Europe.

Procurement, Innovation, and Industry Readiness

The AISRR presents a bold vision for transforming Ireland’s rail system, but achieving this vision will require not just funding, but a rethink of how major infrastructure programmes are delivered. While the AISRR does not prescribe specific procurement models, the complexity, scale, and interdependencies across its recommendations suggest that Ireland will need to move beyond conventional project-by-project contracting toward more integrated and strategic delivery models.

Relevant international examples—such as the UK’s Thameslink Programme and Network Rail’s CP6 enhancements—demonstrate the benefits of programme-based and alliance-style approaches, where long-term frameworks support collaboration, continuous improvement and better risk allocation. These case studies illustrate delivery structures that may be worth adapting for Ireland’s multi-decade rail investment ambitions.

However, adopting such approaches would require strengthening Ireland’s institutional and commercial capabilities. Submissions to the AISRR consultation, including from stakeholders such as Arup, highlighted the need for greater investment in public sector delivery capacity and programme management expertise. Without reforms to governance, procurement practice and skills development within the client ecosystem, even well-scoped projects risk underperformance.

Technological modernisation is another critical pillar in transforming Ireland's rail system. While the AISRR emphasises the need for electrification and service enhancements, achieving high-frequency, low-emission rail services will also require the adoption of enabling technologies. These may include digital signalling systems like the European Train Control System (ETCS), centralised traffic management, smart ticketing and integrated journey planning tools. These technologies are foundational to achieving high-frequency, low-emission rail services, and align with wider objectives under Project Ireland 2040[16] and the National Development Plan 2021–2030[17].

Some groundwork has already begun. Station upgrades at Limerick Junction, platform enhancements at Cork Kent and capacity expansion through the DART+ Programme are progressing. Yet the deployment of full-scale ETCS systems and data-integrated transport platforms remains limited and will require sustained investment and cross-agency coordination.

A further constraint is the readiness of the construction and engineering supply chain. Labour shortages, inflation and skills gaps—particularly in systems engineering and rail operations—pose serious delivery risks. These pressures are compounded by broader competition for skilled workers across housing, energy, water and climate resilience sectors. To avoid bottlenecks, a national delivery capacity strategy is needed, encompassing apprenticeships, training pipelines and small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) enablement. G&T’s Supply Chain Management service on HS2 offers a useful precedent, demonstrating how proactive supply chain mapping and strategic planning can support capacity-building across complex programmes.

Finally, digital transformation must become a delivery norm rather than an afterthought. While Ireland’s broader construction sector has begun to adopt digital tools such as Building Information Modelling (BIM), digital twins and predictive maintenance technologies, the rail sector has yet to fully embed these innovations at scale. Embedding digital approaches into procurement frameworks—through performance-based specifications, whole-life asset metrics, and open data standards—will be critical to unlocking long-term value and operational efficiency.

Conclusion: The Long Game

Ireland’s rail transformation is not just about tracks and trains—it’s about reshaping the economic geography of the country. A 2050 rail network that is electrified, connected and inclusive can serve as the backbone of a green transition, a spatial rebalancing and a productivity surge.

But none of this is automatic. Delivery will require sustained political commitment, rigorous commercial planning and a coalition of public, private, and community actors. If Ireland can maintain momentum through the 2020s, it has a real chance of building a rail system fit for the 21st century—and for the generations that follow.

References

[1] https://www.infrastructure-ni.gov.uk/articles/all-island-strategic-rail-review

[2] ie ensuring all regions have fair access to transport links and development opportunities.

[3] https://www.gov.ie/en/department-of-transport/policy-information/public-transport/

[4] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20241030-1

[5] https://www.irishrail.ie/about-us/iarnrod-eireann-services/freight

[6] https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/cc8fc-all-island-strategic-rail-review/

[7] https://www.irishrail.ie/about-us/iarnrod-eireann-projects-and-investments/investment-new-trains

[8] https://www.dartplus.ie/en-ie/about-dart

[9] https://www.dartplus.ie/en-ie/about-dart

[10] https://logistics.org.uk/logistics-magazine-portal/logistics-magazine-news-listing/auto-restrict-folder/08-02-24/ireland-s-first-road-haulage-strategy-making-progr?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[11] https://www.irishrail.ie/Admin/getmedia/685e9919-f012-4018-879b-06618bb536af/IE_Rail-Freight-2040-Strategy_Public_Final_20210715.pdf

[12] Ie developing the rail network to accommodate Load-on/Load-off (“LoLo”) cargo movements.

[13] https://irishexporters.ie/member_news/the-irish-rail-freight-strategy-2040/

[14] Estimated total capital cost for the interventions presented in the AISRR report range from €35bn/£29bn – €37bn/£31bn in 2023 prices (reflecting the range of the lowest and highest estimates considered).

[15] https://iae.ie/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/IAE_StrategicInfracstucture_Major_Project_Delivery.pdf

[16] https://www.npf.ie/wp-content/uploads/Project-Ireland-2040-NPF.pdf

[17] https://gov.ie/en/department-of-public-expenditure-ndp-delivery-and-reform/publications/national-development-plan-2021-2030/